Social Anxiety and the Fear of Being Judged

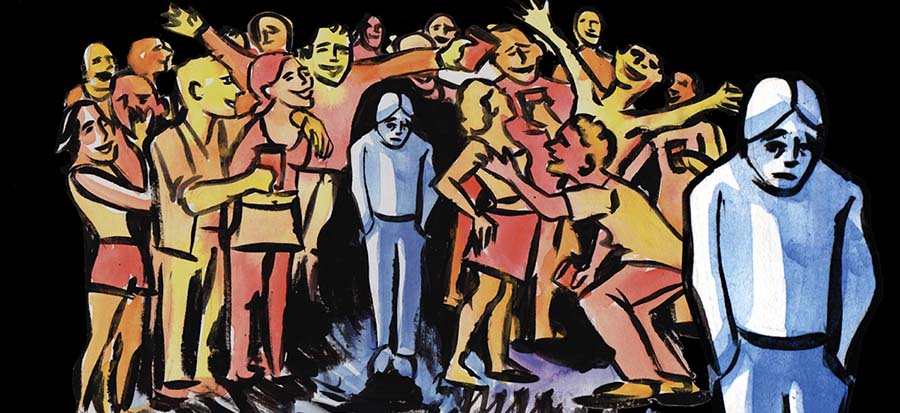

Do you feel an overwhelming fear of being negatively evaluated by others? Do you freeze up or feel deeply uncomfortable in ordinary conversations or everyday interactions? If you find yourself dreading simple social encounters—like meeting new people, answering questions in a group, or even just chatting with a cashier—and this feeling has persisted for six months or more, it might be more than shyness. You could be dealing with social anxiety disorder, a condition that silently disrupts the lives of millions.

Social anxiety disorder, often referred to as social phobia, is a mental health condition marked by a powerful and persistent fear of being judged, humiliated, or rejected in social or performance situations. This isn’t just being a little shy or awkward—it’s a deep-rooted anxiety that can affect every part of life, from work and school to relationships and basic daily tasks. The good news? This condition is highly treatable, and help is available.

Understanding the Nature of Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety disorder falls under the broader category of anxiety disorders and is surprisingly common. Those affected experience strong feelings of fear or dread when placed in social situations. This can occur in specific settings like giving a presentation or meeting new people, or it may span across nearly all interactions, from eating in public to using a shared restroom.

What makes social anxiety so challenging is not just the fear itself, but its intensity and persistence. Individuals often experience physical symptoms—shaking, blushing, nausea, rapid heartbeat—alongside mental anguish, imagining worst-case scenarios and reliving every social moment with self-criticism. The fear feels uncontrollable, as if it’s baked into their identity. It becomes hard to attend school or hold a job, let alone enjoy life’s more casual moments.

People with social anxiety often anticipate these scenarios days or even weeks in advance, mentally rehearsing every detail—and more often than not, avoiding the event altogether. They might skip parties, job interviews, weddings, or other important milestones simply out of fear they’ll embarrass themselves or be seen as inadequate.

Interestingly, not everyone with this disorder fears every kind of social engagement. Some individuals only feel intense anxiety during public performances—like giving a speech, competing in sports, or playing music in front of others. This form is known as performance-only social anxiety, and though narrower in scope, its effects can be just as paralyzing.

This disorder most often begins in adolescence, particularly among those who were extremely shy as children. According to research, nearly 7% of the U.S. population lives with some form of social anxiety. Unfortunately, without proper treatment, this condition can become a lifelong struggle, holding people back from reaching their full potential in work, relationships, and personal growth.

Common Signs and Symptoms of Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety isn’t just garden-variety nervousness. It’s a persistent and exaggerated fear that interferes with everyday functioning. While many people feel uneasy in unfamiliar situations, individuals with social anxiety experience disproportionate stress before, during, and after any event involving interaction.

Here are some of the hallmark symptoms you might recognize:

-

Constant worry about day-to-day activities like speaking on the phone, starting small talk, eating at a restaurant, or going shopping.

-

Avoidance of social events such as dinner parties, group projects, or informal meet-ups.

-

Intense fear of doing anything that could be interpreted as awkward or embarrassing—such as blushing, stumbling over words, sweating, or appearing “off.”

-

Difficulty performing tasks while being observed—feeling as if everyone is watching and judging your every move.

-

Deep fear of being criticized or ridiculed, which often leads to avoiding eye contact and experiencing crushing self-doubt.

-

Frequent physical symptoms like upset stomach, sweating, trembling, racing heart, or even nausea when faced with social interaction.

-

Panic attacks—sudden, intense episodes of fear that can include chest tightness, dizziness, and the sensation of being out of control—often triggered by specific social situations.

Many individuals with social anxiety also deal with other overlapping mental health conditions, such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or panic disorder. This layering can make it even harder to distinguish the root cause without professional guidance, but it also means multiple pathways for treatment and support are available.

A Glimpse Into What Social Anxiety Feels Like

Here’s a snapshot of what daily life might feel like through the eyes of someone with social anxiety:

“In school, I’d dread being called on by the teacher. Even if I knew the answer, my mouth would dry up and my heart would start pounding. I couldn’t focus on anything except the thought of being laughed at or looking dumb. Later, when I entered the workforce, the same feelings followed me into meetings and one-on-one chats with my boss. I even skipped my best friend’s wedding reception—not because I didn’t care, but because I couldn’t face the crowd.

At some point, I started drinking before events just to calm my nerves. But the drinking turned into a daily crutch, and I knew something had to change. Eventually, I got help—therapy, medication, and a lot of internal work. I still get anxious, but I’ve learned how to manage it. I’m not hiding anymore.”

This personal story echoes the reality for many who live with social anxiety. It’s not about lacking confidence or being anti-social—it’s about struggling with a deeply ingrained fear that distorts how you see yourself and how you assume others perceive you.

Where Does Social Anxiety Come From? Exploring Its Roots

Social anxiety disorder doesn’t have a single cause. Like many mental health conditions, it arises from a complex mix of genetics, brain function, upbringing, and life experience.

It often runs in families, although researchers still aren’t sure why some family members develop it while others don’t. Some studies suggest that the amygdala—the part of the brain responsible for processing fear—might be overactive in people with social anxiety. This heightened sensitivity can make ordinary situations feel threatening or overwhelming.

There’s also evidence that misreading other people’s behavior plays a role. If you’re someone who consistently assumes others are disapproving, mocking, or judging you—even when they aren’t—you’re more likely to experience social anxiety. These distorted thoughts reinforce avoidance and fear.

Another contributing factor may be underdeveloped social skills. For example, if you grew up avoiding conversation, you might lack practice or confidence in interacting with others. One awkward experience can snowball into a pattern of fear and self-criticism, making it harder to try again next time.

Environment matters too. Bullying, overly critical parenting, or a traumatic public embarrassment can lay the groundwork for social anxiety later in life. While not everyone who has these experiences develops the disorder, they certainly increase the risk—especially when paired with genetic sensitivity.

By continuing to study the brain’s fear circuits and how our thoughts shape behavior, researchers hope to uncover more effective treatments and earlier interventions.

Practical Ways to Start Managing Social Anxiety Yourself

If you’re dealing with social anxiety, you’re not alone—and you're not without options. While professional treatment is often necessary for long-term relief, self-help strategies can be a valuable stepping stone. In fact, many people start by working on themselves before taking the next step toward therapy or medication.

Here are a few strategies that may help you gradually ease your anxiety and regain a sense of control:

-

Learn more about your anxiety by tracking it – Keep a small notebook or digital journal to jot down your thoughts and reactions in different social settings. Note what triggered your anxiety, how you responded, and how you felt afterward. This reflection can help you identify patterns and understand what exactly feeds your anxiety.

-

Practice relaxation techniques – Breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, or even guided mindfulness meditations can slow your heart rate and help ground you during high-stress moments. When used consistently, these techniques retrain your body’s response to stress.

-

Break challenges into manageable pieces – For instance, instead of forcing yourself to give a speech to a group, start by rehearsing it in front of a mirror, then in front of one trusted friend, and so on. Exposure to social situations in a controlled, gradual way can build confidence over time.

-

Redirect your attention – Rather than being caught up in your inner critic during social interactions, practice really listening to others. Try to focus on what’s being said instead of how you’re being perceived. People are usually more focused on themselves than on judging you.

These small but consistent actions can weaken the grip of social anxiety, especially when practiced with self-compassion and patience.

When Should You Reach Out for Help?

If social anxiety is holding you back—impacting your job, relationships, or daily functioning—it’s time to consider getting professional support. There’s no shame in asking for help. In fact, taking that first step might be the most courageous thing you ever do.

A good place to start is with your primary care provider or general practitioner. They can ask the right questions to better understand your symptoms, how long you’ve had them, and how they’re affecting your life. These discussions help rule out physical conditions and guide referrals to mental health professionals.

If you're in the UK, you also have the option of self-referring directly to an NHS psychological therapies service (also known as IAPT) without going through a GP. This can streamline your access to therapy and reduce the pressure of explaining yourself in multiple appointments.

During the assessment process, you’ll likely speak with a psychologist, psychiatrist, or trained counselor who will help you explore treatment options best suited to your needs.

What’s important to remember is this: Social anxiety is treatable. You're not destined to live with it forever. Taking that first step toward understanding and support is a powerful move toward reclaiming your freedom.

How Social Anxiety Disorder Is Typically Treated

Once diagnosed, social anxiety disorder is most commonly treated through a combination of therapy, medication, or both. The exact treatment plan will depend on your specific symptoms, preferences, and medical history—but many people find relief with time and consistency.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): The Gold Standard

The most effective type of psychotherapy for social anxiety disorder is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). This approach helps rewire the brain’s automatic responses to social stress. It teaches you how to challenge distorted thoughts, adjust unhelpful behaviors, and adopt healthier coping strategies.

CBT often includes role-playing exercises, journaling, and exposure tasks designed to gradually desensitize you to feared situations. Over time, your mind begins to reframe social experiences in a more neutral or even positive light.

Group CBT can also be highly beneficial. When done with others who have similar fears, it creates a supportive space for practicing social interactions and gaining objective feedback—something that individual therapy can’t always provide.

Support Groups and Peer Sharing

Many individuals also find value in support groups where they can meet others who understand what they’re going through. These communities foster a sense of belonging and can help you see that your fears are shared—not unique or irrational. Within these groups, you can hear real stories of progress and learn creative strategies others have used to confront similar challenges.

Support groups can be peer-led or guided by a therapist, and they often meet online or in person.

Medications for Social Anxiety: What to Know

Medications can be a helpful adjunct to therapy, especially when symptoms are severe. There are three main categories typically prescribed:

-

Anti-Anxiety Medications

Fast-acting and effective at reducing acute symptoms, these drugs (often benzodiazepines) work well in the short term. However, they carry a risk of tolerance and dependence, so they’re not usually recommended for long-term use. Doctors often reserve these for situational use or severe flare-ups. -

Antidepressants

Specifically, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed for social anxiety. They don’t work immediately—it may take several weeks—but they’re effective at reducing overall anxiety over time. Side effects like nausea, insomnia, or headaches are possible but often mild and temporary. Starting on a low dose and adjusting slowly is the typical strategy. -

Beta-Blockers

Unlike the other two, beta-blockers don’t target emotional symptoms directly. Instead, they suppress the physical symptoms of anxiety—such as trembling hands, rapid heartbeat, or sweating. They're often used in performance-related social anxiety, like stage fright or public speaking.

Your doctor will help determine the right combination of medication (if any), dose, and duration. Some people find therapy alone sufficient, while others benefit most from combining it with pharmacological support.

Building a Healthier Lifestyle to Support Recovery

While therapy and medication are vital tools, your lifestyle plays a huge role in how you manage anxiety. Here are some things you can do to reinforce your recovery:

-

Sleep well – Poor sleep increases stress hormones and worsens anxiety. Aim for 7–9 hours of quality rest per night.

-

Eat a balanced diet – Nutrient-rich foods support brain function. Limit caffeine and sugar, which can spike anxiety.

-

Stay physically active – Exercise helps regulate mood, release tension, and boost self-esteem.

-

Connect with others – Whether it’s friends, family, or a support group, surrounding yourself with trusted people can offer reassurance and motivation.

Social anxiety disorder may feel like a heavy burden, but it’s not a life sentence. With the right knowledge, support, and treatment, you can reduce its impact and learn to move through the world with greater ease and confidence—step by step, day by day.