How Habits and Feelings Shape Our Decisions

We make countless decisions throughout our day—some big, some tiny, some that we’ll forget before they’re even over. And though we often like to believe we’re being rational, clear-headed thinkers, many of those decisions are far from logical. In fact, there's an ongoing debate in psychology and neuroscience that suggests most—if not all—decisions are ultimately driven by emotion.

Emotion Often Sits at the Core of Every Decision

-

Even in cases where we think we’re acting logically, it’s emotion that often determines which option we ultimately go with.

-

This realization changes the game for anyone in negotiation or marketing. If you think pure logic is enough to persuade someone, you're likely missing the true motivators behind their decisions.

-

Brain injury studies show that people with damage in the emotional centers of the brain often struggle with decision-making altogether, even when their logical faculties remain intact.

The Case of Kelly and the Chatbot Subscription

Kelly is responsible for IT services at her company. Among her tasks is managing subscriptions, including a chatbot service the company has been using at the “Pro” level for two years. Now it's time to renew. What will she do?

Will she keep the “Pro” level? Downgrade to the free version? Cancel entirely?

Her decision may be influenced by the tone of the renewal email, the presentation of the pricing on the service’s website, or even how easy it is to click “renew.”

And here's the thing—her choice likely won’t come down to features and benefits alone.

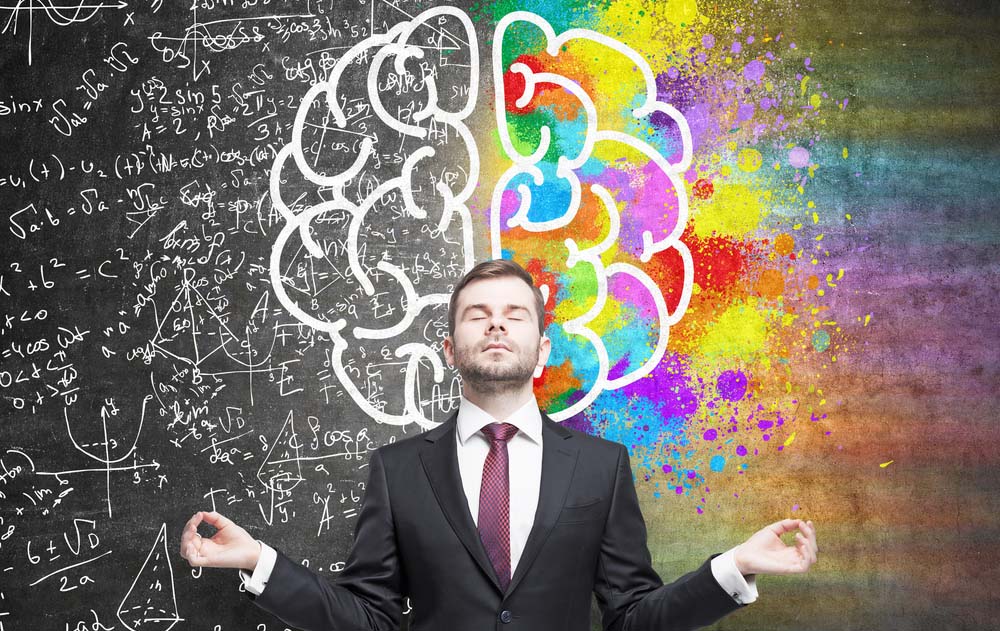

The pricing options that Kelly sees on her renewal page.

Insights From Behavioral Science on Decision-Making

The way humans make decisions isn’t just an interesting topic for philosophers or psychologists—it’s become a goldmine of discovery across several disciplines, including neuroscience, behavioral economics, cognitive psychology, and even marketing. Every day, we make hundreds of choices—most without even realizing it. What we wear, what we eat, what we click, what we buy… and beneath all of it lies a complex, often unconscious process that drives human behavior.

Contrary to the classic notion of humans as rational agents—those who calculate risks and benefits with perfect clarity—modern research paints a more intricate picture. Decades of experimental studies and brain imaging have revealed that we are not nearly as rational as we believe we are. In fact, many of our decisions are predictable in their irrationality, guided not by careful analysis but by emotion, mental shortcuts, and deeply embedded cognitive biases.

One key turning point in this field came from the work of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who demonstrated that people rely on heuristics—mental rules of thumb—to make decisions quickly, especially under uncertainty. These shortcuts help us survive in a world overflowing with information, but they also lead to systematic errors, like confirmation bias or loss aversion. Kahneman later won the Nobel Prize for this work, which helped launch the entire field of behavioral economics.

Behavioral scientists have also studied how context, framing, priming, and emotional state can drastically alter the choices we make. The same product presented as “90% fat-free” is more appealing than one labeled “10% fat,” even though they are identical. A person who just watched a sad movie may be more prone to make generous donations than someone who’s emotionally neutral. These findings aren't just trivia—they're foundational principles used in everything from advertising to public health campaigns.

And let’s not forget about habit and automaticity. Many of our daily choices—perhaps the majority—aren’t active deliberations at all. They're habits, born of repetition, convenience, and emotional safety. We don’t think through every step of brushing our teeth or choosing a familiar brand—we just do it. These routine behaviors often feel like decisions, but they happen in the background, barely touching our conscious awareness.

In short, the idea of the purely logical decision-maker is more myth than reality. And understanding this helps us not only influence others' choices more effectively, but also understand our own behaviors better. Whether it’s a business looking to increase conversions, a designer creating user flows, or an individual just trying to make better life choices—the study of how we make decisions is no longer optional. It’s essential.

Logical Thinking Is Rarely the True Driver Behind Decisions

We often like to imagine that when we're buying a car, choosing a job, or picking out software, we go through all the specs, read every review, and make an informed choice. But in reality, most decisions aren’t as deliberate as we think.

Take Kelly again. Does she really go back and evaluate how her company used the “Pro” chatbot service over the past year before renewing? Or does she just click “renew” out of habit, a sense of comfort, or fear of the unknown?

Even when the stakes are high, most of our choices—big or small—are shaped by emotional cues and unconscious reactions. We just rationalize them after the fact.

Most Decisions Happen Before We Even Realize It

Brain scan studies show something mind-bending: researchers can often predict a person’s decision 7 to 10 seconds before the person becomes consciously aware of it.

That means even when you feel like you're thinking something through, your brain might have already made the decision behind the scenes. And you, the conscious “you,” are just catching up.

Are You Appealing to Logic in Your Messaging?

If your business communications rely on logical persuasion alone—bullet points about features, rational pricing comparisons—you might be missing the emotional trigger that causes someone to act.

Be Cautious When Listening to What People Say

Humans love to give “logical” explanations for their actions—even when those explanations aren’t the real reason.

If someone asked Kelly why she sticks with the “Pro” level, she might say it's because of advanced features or company needs. But deep down, it might simply be fear of tech failures, or the comfort of familiarity.

Emotion Is Necessary for Decision-Making

Thanks to a region in the front of the brain called the ventro-medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), humans are able to regulate fear and make emotionally informed decisions. Without it, we literally struggle to choose.

While the amygdala tells us what to be afraid of, the vmPFC helps us move past those fears. If it’s inactive, we can become paralyzed with indecision.

This is why understanding how someone feels about a choice is just as important—if not more important—than what they think about it.

So instead of trying to win Kelly over with technical specs, it might be more powerful to reassure her emotionally. If she’s worried about service failure, emphasizing reliability and support could do far more than showing a list of features.

Confidence Triggers Action

Inside the brain, certain neurons fire only when a person feels confident about a decision. This isn't about logic or evidence—it's about the emotional sense of certainty.

If you want someone to take action, you have to give them that emotional nudge toward confidence. In Kelly’s case, that could mean reminding her of how much her team has benefited from the “Pro” plan in the past—giving her a feeling of reassurance, not just rational data.

Don’t Mistake Unconscious Decisions for Poor Ones

Some authors argue that unconscious decisions are irrational or flawed. Dan Ariely, for example, in Predictably Irrational, suggests that without checks and balances, most of our decisions lean toward the illogical.

But this doesn’t give the unconscious mind enough credit.

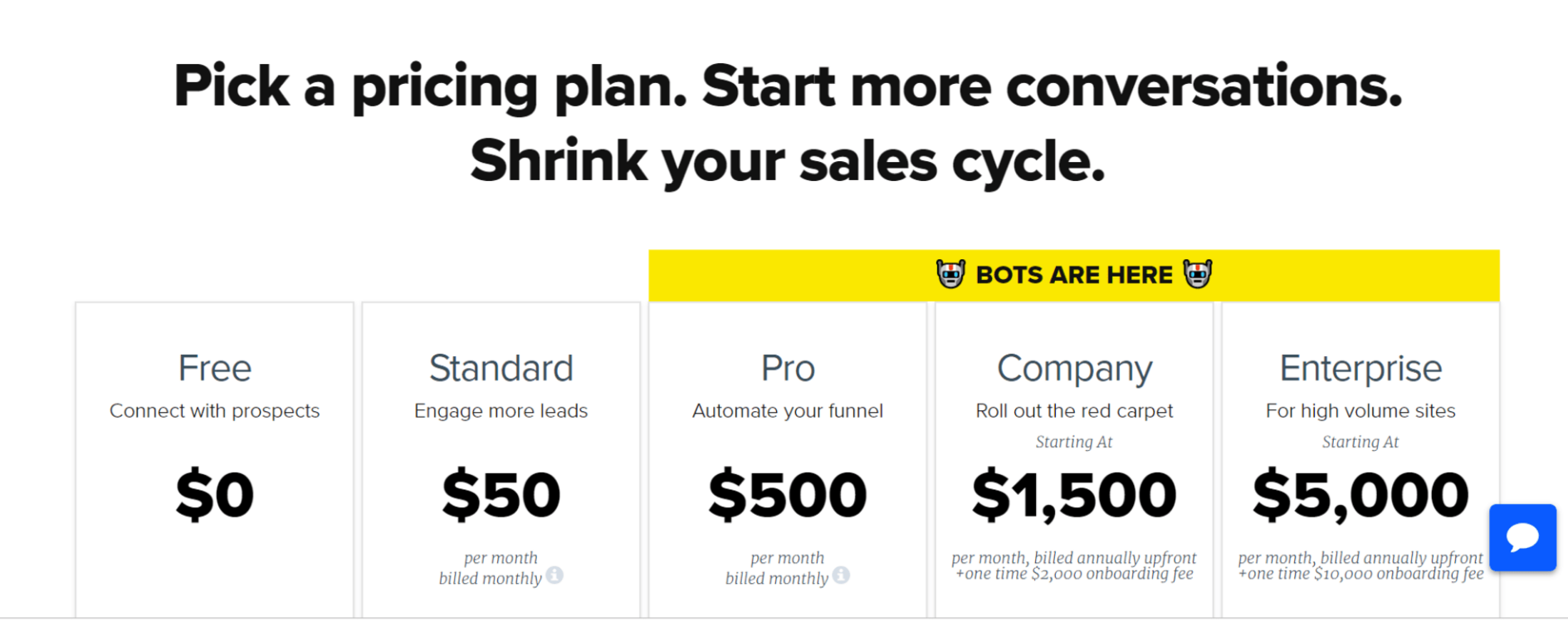

According to Dr. Timothy Wilson, we’re bombarded with over 11 million pieces of data every second. Our conscious brain can’t process all of that—so we rely on our unconscious to sort, prioritize, and decide.

These unconscious systems have evolved to keep us alive and functioning efficiently. They operate based on shortcuts, learned rules, and emotional tagging—all of which usually work in our favor.

So yes, Kelly might renew the chatbot subscription without a formal review. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a bad choice. Her gut feeling—formed by two years of familiarity and a lack of issues—might be doing exactly what it was designed to do.

In reality, people like to feel that they are making rational choices. So giving them some logical reason—however thin—to support an emotionally-made decision helps them feel justified. Kelly may already be sold emotionally, but offering her a logical-sounding reason helps her explain it to her boss, her team, or even herself.

Goal-Based vs. Habit-Based Decisions: A Battle in the Brain

When people make choices, they’re not always weighing pros and cons with a spreadsheet open in front of them. In fact, most decisions happen in one of two modes: goal-driven or habitual. And which system gets activated can drastically change the way we should communicate with people.

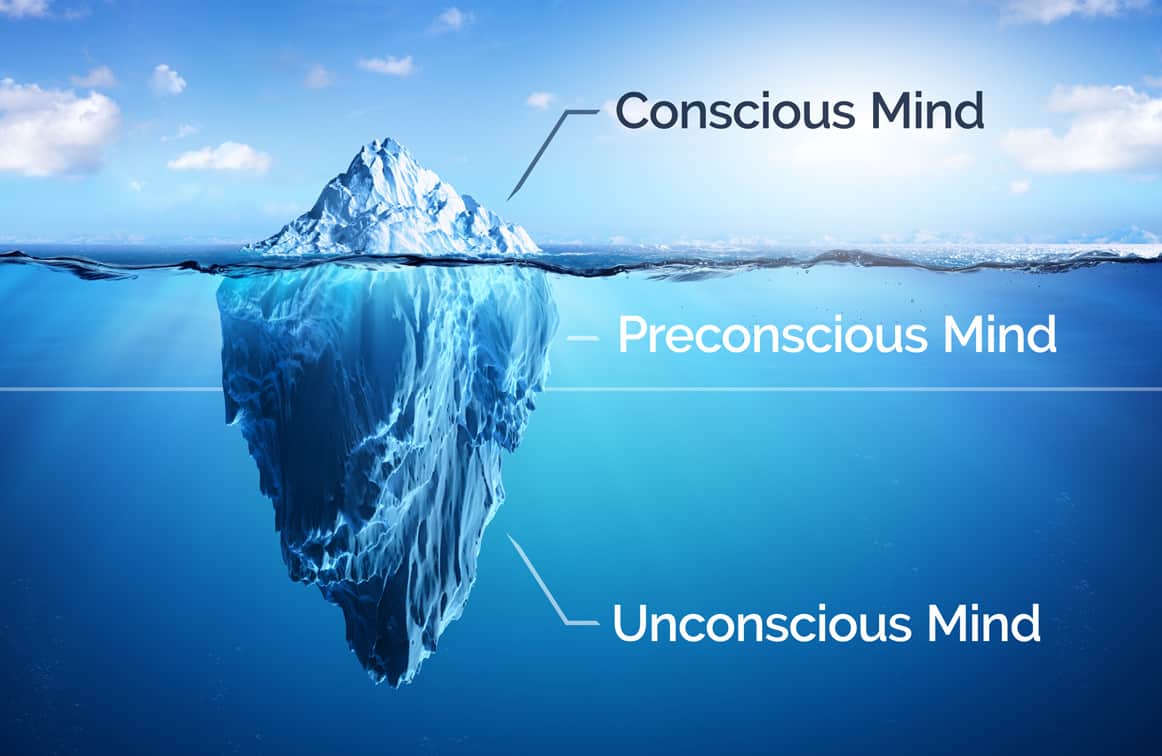

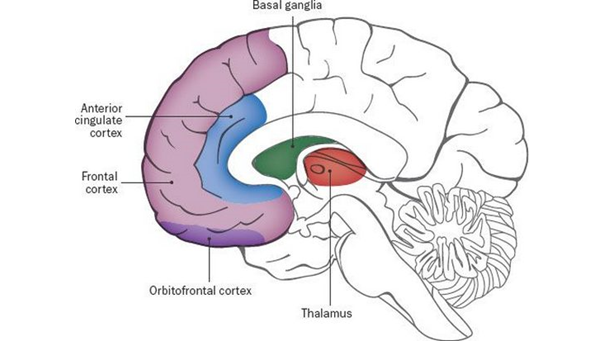

The Brain’s Decision Zones

-

Value-Based (Goal-Directed) Decisions

These are handled by the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC)—a part of the brain that kicks in when we’re comparing options to pursue a particular goal. For instance, when someone is test-driving both a Honda and a Subaru, reading reviews, and mentally checking boxes, that’s the OFC hard at work.

If Kelly were seriously comparing the chatbot service tiers—evaluating support speed, user satisfaction, or feature lists—she’d be making a value-based decision.

-

Habitual Decisions

These are formed deep in the brain, inside the basal ganglia. These are the decisions that happen on autopilot: grabbing the same cereal every week, using the same password for every account, or clicking “renew” without second-guessing.

So when Kelly simply hits the renew button for the chatbot service without thinking too hard, that’s a habit-based choice driven by the basal ganglia.

Structure of the human brain showing where the basal ganglia reside—our habit engine.

Only One System Works at a Time

One fascinating thing researchers have discovered is that people don’t use both systems simultaneously. When the OFC is activated, the habit system goes quiet—and vice versa.

This has huge implications for decision design. If you want someone to make a goal-driven decision, give them information—details, comparisons, explanations.

But if you want to trigger a habit-based decision, it’s better to keep things simple and automatic.

Let’s bring it back to Kelly again. If your aim is for her to just stick with her current plan, don’t throw a bunch of details at her. That could actually switch her brain into goal-analysis mode and risk her reconsidering. Just offer a gentle prompt and let the habit do the work.

But if you want her to upgrade, then yes—show her the data. Get her brain into the “let’s compare” mode. That’s when she might actually consider a new option.

The Danger of Overloading With Options

Now let’s talk about something we all face, especially online: too many choices.

You’ve seen it: 10 pricing tiers. 12 different add-ons. A drop-down menu that never ends. While it feels like offering “more” gives people power and flexibility, research shows the opposite is true.

The 7±2 Myth Debunked

Many people believe that the average person can hold 5 to 9 items in short-term memory. This idea came from psychologist George Miller back in 1956. But since then, plenty of studies have shown that’s more myth than fact.

In reality, the brain can truly juggle about 3 to 4 items in working memory before things start falling apart.

Here are just a few research pieces that dismantle the old theory:

-

The Magical Number 4 In Short-Term Memory — Nelson Cowan (2001)

-

The Magical Number Seven: Still Magic After All These Years? — Alan Baddeley (1994)

-

The Magic Number Seven After Fifteen Years — Donald Broadbent (1975)

But perhaps the most impactful research came from Sheena Iyengar, author of The Art of Choosing. She ran a series of choice experiments where participants were offered varying numbers of product options.

Result?

People enjoyed having more choices…

…but were far more satisfied when they picked from a smaller set.

Too many choices trigger decision fatigue, anxiety, and even inertia—which means people often end up not choosing anything at all.

What Does That Mean for Kelly?

In the chatbot example, Kelly was shown five different plan options. That may not seem like a lot, but it’s enough to risk indecision. Had she been given three, it’s far more likely she would have simply clicked her preferred one without overthinking it.

So, if you want someone to follow through—especially on a habit-based decision like a renewal—the fewer choices, the better.

What’s the Best Way to Nudge a Decision?

If your goal is to keep Kelly at her current plan level, don’t flood her inbox with information. Skip the full feature breakdown of every option. Just give her one or two gentle cues to keep doing what she’s always done.

Something like:

“Your current plan continues to offer everything your team needs. No action needed—your subscription will renew automatically.”

That reinforces the existing pattern without encouraging scrutiny.

But if you’re hoping to push her up a tier, timing and design matter.

Don’t pitch the upgrade when she’s already about to renew—that’s habit time. Instead, reach out at a different time in the cycle with comparisons, testimonials, or usage reports. That way, you engage her OFC rather than interrupting her habit loop.

Key Principles to Guide Strategic Decision Design

-

When someone is leaning on habit, less information is better.

-

People want to feel like their choice is logical, so give them a short and clear justification—even if their real motivator is emotional.

-

Offering three options or fewer increases the chances they’ll choose at all.

-

If you want someone to make a thoughtful, goal-driven decision, introduce details, comparisons, and messaging that activates curiosity or evaluation.

In essence, help people feel good about their choice, while keeping the decision path clear and uncluttered. The human mind isn’t a robot built on logic. It’s a beautifully messy, emotionally driven, shortcut-taking machine—and understanding that gives you the upper hand in guiding it.