20 Brilliant Minds That Transformed Philosophy Forever

Every era has its visionaries—those rare individuals who dared to question the obvious, dismantle old beliefs, and construct bold new ideas about life, reality, truth, and the human condition. These weren’t just thinkers confined to ivory towers. They were revolutionaries of the mind, shaking the foundations of how we perceive everything from existence to ethics, from knowledge to power.

The history of philosophy isn’t just a long list of abstract theories. It’s a living, breathing dialogue across centuries. Each philosopher builds upon or reacts to those before them, creating a vast intellectual tapestry. Some wrote in dense, cryptic prose; others spoke plainly. Some changed the world with a single sentence. All of them left fingerprints on how we think today.

This article is not a dry chronology of names and dates. It’s a curated journey through 20 of the most influential philosophers the world has known—Western and Eastern alike—along with the core ideas that defined their legacy. Whether you’re just dipping your toes into the world of philosophy or you’re looking to deepen your appreciation, this guide will introduce you to the thoughts that have shaped civilizations, challenged worldviews, and continue to inspire deep reflection.

From Plato’s vision of ideal forms to Foucault’s critique of power , from Confucius’ moral wisdom to Nietzsche’s philosophical thunder, these thinkers didn’t just ask big questions—they reshaped how we even ask them.

Let’s begin.

Socrates (469–399 BCE)

Socrates never wrote down a single philosophical treatise, but his impact is legendary. He roamed the streets of Athens engaging in public discussions, usually in the form of relentless questioning. This method—now called the Socratic Method—was less about giving answers and more about exposing ignorance. His idea? That true wisdom begins with admitting that we know very little.

Socrates believed that ethical behavior was tied to knowledge. If a person truly knew what was right, they would do it. Therefore, moral failure wasn't necessarily due to weakness but due to ignorance. He also championed the importance of self-examination, famously declaring, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”

Despite making enemies in powerful places, Socrates refused to flee Athens when he was sentenced to death. He drank poison hemlock and died as a martyr for reason and inquiry.

For a soft entry into his methods, we quite like 'conversations of Socrates'!

Plato (427–347 BCE)

Plato, a student of Socrates, did what his mentor never did—he wrote down ideas, and lots of them. His dialogues are foundational to Western philosophy. One of his most influential concepts is the Theory of Forms—the belief that the physical world is only a shadow of the true reality, which consists of ideal, unchanging forms or ideas.

He also envisioned a just society in his famous work The Republic, proposing that philosopher-kings—those ruled by reason rather than desire—should lead. Education, he believed, was the key to building both the soul and the state.

Plato founded the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. His influence echoes through nearly every corner of philosophy, from metaphysics to ethics to political theory.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

A student of Plato but no copycat, Aristotle preferred looking at the tangible world instead of abstract ideals. He was one of history’s most methodical thinkers, pioneering the field of logic, formalizing syllogisms, and laying the groundwork for scientific classification.

In ethics, Aristotle introduced the idea of the Golden Mean—that virtue lies between extremes. Courage, for example, exists between cowardice and recklessness. He believed human happiness (eudaimonia) was the ultimate goal, achievable through rational activity and the cultivation of virtue.

His influence spans multiple disciplines—biology, physics, politics, poetry, drama, and beyond. For centuries, Aristotle was the authority in nearly every scholarly field.

We encourage you to check out Nicomachean Ethics for a start point into his ideas.

Confucius (551–479 BCE)

Confucius wasn’t just a philosopher—he was a cultural architect. His teachings formed the backbone of Chinese thought for over two millennia. He emphasized social harmony, moral duty, and respect for hierarchy. His philosophy revolved around the importance of li (ritual), ren (benevolence), and xiao (filial piety- or respect to one's ancestors).

Confucius believed that good governance started with good people. If rulers were virtuous, the people would follow. He didn’t promote revolution or rebellion; he promoted internal reform, family values, and a society built on mutual respect.

His Analects, a collection of sayings compiled by his followers, still guide moral and political thought in much of East Asia.

René Descartes (1596–1650)

Descartes was a man who doubted everything—on purpose. He stripped away every belief he had until he found one undeniable truth: “I think, therefore I am.” This statement became the cornerstone of rationalism, the belief that reason is the primary source of knowledge.

He envisioned the universe as a grand machine, governed by mathematical laws. In doing so, he helped separate science from religion, paving the way for the Scientific Revolution. Descartes also proposed mind-body dualism, the idea that the mind and body are distinct entities. This notion still fuels debates in philosophy of mind today.

While Descartes was trained in classical scholasticism, his method of radical doubt made him a father of modern philosophy. You can see that in his collected works here!

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

Immanuel Kant completely reshaped how we think about knowledge, morality, and the nature of reality. In his groundbreaking work Critique of Pure Reason, he argued that our understanding of the world is filtered through the structures of the human mind. According to him, we never experience reality “as it is”—instead, we perceive a version of reality shaped by our senses and cognition.

In ethics, Kant introduced the Categorical Imperative, first presented in his book 'Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals', is a principle that says we should act only in ways that could become universal laws. In other words, don’t lie unless you’re okay with everyone lying all the time. For Kant, morality wasn’t about outcomes—it was about duty, intention, and respect for rational beings.

He also believed in human autonomy and that people should never be treated merely as a means to an end. Kant’s legacy is foundational in both moral philosophy and epistemology.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900)

Nietzsche was a bold and fiery thinker who often wrote like a poet, not an academic. He challenged nearly every philosophical tradition before him, famously declaring first in 'The gay science' that “God is dead”—not as a triumph, but as a warning about the decline of shared moral frameworks in a post-religious society.

Nietzsche's concept of the Übermensch (Overman or Superman) represented an individual who creates their own values and lives authentically in a chaotic world. He also criticized herd mentality and conventional morality, which he saw as suppressing human creativity and vitality.

In works like Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche questioned truth, morality, and the purpose of life. Though controversial, his work remains influential in existentialism, psychology, and postmodern thought.

John Locke (1632–1704)

Often called the "Father of Liberalism," John Locke laid the philosophical groundwork for modern democracy and human rights. His theory of natural rights—life, liberty, and property—would go on to inspire political revolutions, most notably the American Declaration of Independence.

Locke was a key figure in empiricism, arguing that the human mind begins as a blank slate (tabula rasa), shaped by experience. This idea was revolutionary because it challenged notions of innate knowledge and divine rule.

In Two Treatises of Government, Locke promoted the idea of a social contract—the belief that governments exist only with the consent of the governed and can be overthrown if they fail to protect basic rights.

David Hume (1711–1776)

David Hume was a skeptic through and through. He took empiricism to its extreme, arguing that all knowledge stems from sensory experience. Anything beyond that—like metaphysics or religion—he viewed with suspicion.

One of his most powerful contributions was his critique of causality. He argued that we never truly observe cause and effect; we only assume it because we see patterns. Just because the sun rose yesterday doesn’t prove it will tomorrow. This radical doubt influenced later philosophers, including Kant.

In ethics, Hume argued that reason alone can’t motivate action—our emotions and passions play a central role. His is-ought problem (later dubbed Hume’s Guillotine) laid out in Treatise of Human Nature still sparks debates about how we derive moral principles from factual statements.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)

Rousseau believed that civilization corrupts natural goodness. In his view, people are born pure and free, but society imposes chains that warp and restrict their humanity. His most famous line—“Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains”—sets the tone for his philosophical mission.

In The Social Contract, he proposed that legitimate political authority comes from a general will—the collective will of the people aimed at the common good. He also argued that private property was the root of social inequality.

Rousseau’s ideas deeply influenced the French Revolution and modern democratic thought. His emphasis on emotion, authenticity, and human dignity also made him a key precursor to the Romantic movement and existentialism.

Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855)

Often referred to as the father of existentialism, Søren Kierkegaard focused on the inner life of the individual—particularly the tension between faith, doubt, freedom, and despair. Living in a deeply Christian society, Kierkegaard challenged both the institutionalized church and the superficial religiosity of his time.

His central idea was that truth is subjective. He believed that religious belief isn’t something that can be proven or reasoned into—it’s a leap of faith, a personal choice that defines one’s very existence. In works like Fear and Trembling and The Sickness Unto Death, he explored themes like anxiety, despair, and what it means to truly live with authenticity.

Kierkegaard’s reflections laid the groundwork for later existentialists like Sartre and Camus, but his deeply spiritual orientation also keeps him rooted in Christian theology.

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951)

Wittgenstein revolutionized the philosophy of language—not once, but twice. His early work, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, asserted that the structure of language mirrors the structure of reality, and that philosophical problems arise from the misuse of language.

But years later, in his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein dramatically revised his views. He now argued that language is a form of life, deeply embedded in social practices. Words gain meaning not from strict definitions, but from how they are used.

This shift helped create the ordinary language philosophy movement, and his thinking remains influential in everything from cognitive science to literary theory.

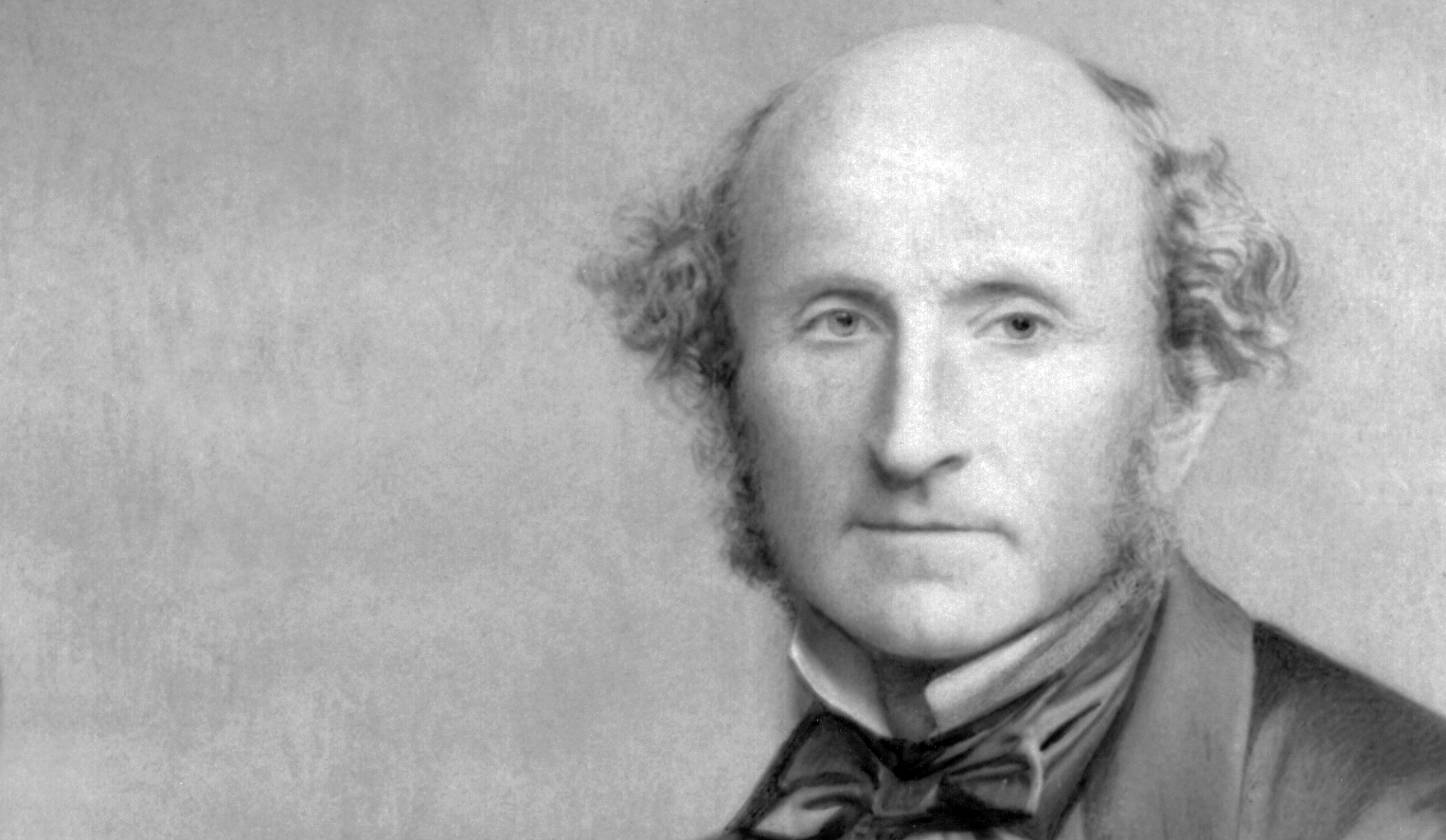

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873)

John Stuart Mill was a champion of individual liberty and a leading figure in the development of utilitarianism—the ethical view that actions are right if they promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

In On Liberty, Mill passionately defended freedom of speech and individual autonomy, believing that society should only restrict behavior if it causes harm to others. He also advocated for women’s rights, a radical stance for his time, and pushed for universal education and democracy.

Unlike earlier utilitarians, Mill emphasized qualitative differences in pleasure, believing that intellectual and moral pleasures were superior to mere physical gratification.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831)

Hegel developed one of the most complex philosophical systems ever created. Central to his thought was the idea of dialectics—the process by which contradictions resolve themselves into higher truths. In simple terms, he believed that history and human understanding evolve through a cycle of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

Hegel saw reality as a rational unfolding of the Absolute, a kind of all-encompassing Spirit or Mind realizing itself over time. His philosophy attempted to reconcile opposites—freedom and necessity, individual and society, subject and object.

Though dense and difficult, Hegel’s work influenced nearly every major thinker after him, including Marx, Nietzsche, and Heidegger. His belief that ideas shape history helped bridge idealism with historical materialism.

2 Key works of his would be 'Phenomenology of spirit' & 'Science of Logic'

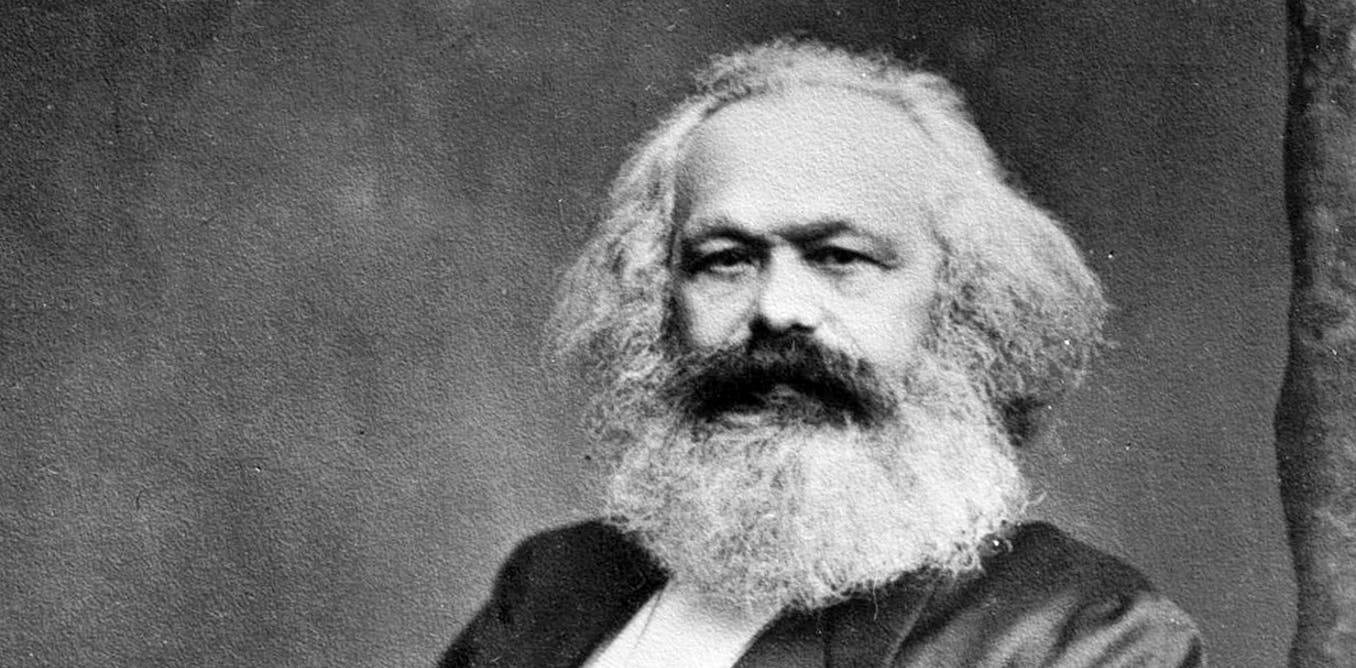

Karl Marx (1818–1883)

Marx took Hegel’s dialectics and gave them a revolutionary twist—materialism instead of idealism. Rather than history being driven by ideas or spirit, Marx argued that material conditions and economic relations were the true engines of change.

His core idea, known as historical materialism, holds that all human history is the story of class struggle. From feudalism to capitalism and, eventually, to communism, Marx saw society evolving through conflict between oppressors and the oppressed.

In 'The Communist Manifesto' and 'Das Kapital', Marx predicted the collapse of capitalism and the rise of a classless society. Though his predictions remain controversial, his influence on economics, politics, and philosophy is undeniable.

Albert Camus (1913–1960)

Philosopher, playwright, suave chain-smoker....Albert Camus pioneered the concept of absurdism in his time, being the 2nd youngest Nobel prize winner in literature at that point in history. Seen as the bridge between existentialism and nihilism, Camus' absurdist viewpoint acknowledged man's struggle for meaning in a meaningless universe. His perspective was that neither side of the equation will change, but that shouldn't stop man from engaging and enjoying life to the fullest.

And engage with life Albert did, having written numerous novels and plays focusing on the idea of 'deep, moral living'. Rather than to surrender the eternal struggle for meaning, in 'The Myth of Sisyphus' Camus makes it clear the only viable choice is 'the revolt'- living with the constant awareness of lifes inherent meaningless, and enjoy oneself in the face of it.

His landmark novel 'The Stranger', despite its' bleakness, is a beautiful point made that true liberation comes with realising the world doesn't care. And when you accept this, life begins.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980)

Sartre was a central figure in existentialism—a movement that placed human freedom, responsibility, and subjectivity at the core of philosophical inquiry. In 'Being and Nothingness', he argued that existence precedes essence—we are not born with a predefined purpose; rather, we create ourselves through our choices and actions.

This freedom, however, is a double-edged sword. Sartre emphasized the burden of freedom, the weight of creating one’s own meaning in a universe that offers no inherent guidance.

He was also politically active, embracing Marxism and opposing colonialism, and his play 'No Exit' gave us the famous line: “Hell is other people.” Sartre’s life and work continue to spark discussions on freedom, authenticity, and self-deception.

Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986)

A philosopher in her own right and partner of Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir broke philosophical ground in feminism, existentialism, and ethics. Her landmark work, 'The Second Sex', asked: “What is a woman?” and answered with radical clarity: women have historically been defined as the “Other,” as secondary to men.

Beauvoir argued that gender is not a destiny, but a social construct—“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Her existential framework emphasized freedom, responsibility, and becoming, and she insisted that both men and women must transcend restrictive roles to live authentically.

She helped launch second-wave feminism and expanded existential thought into areas of gender, identity, and social justice that continue to resonate today.

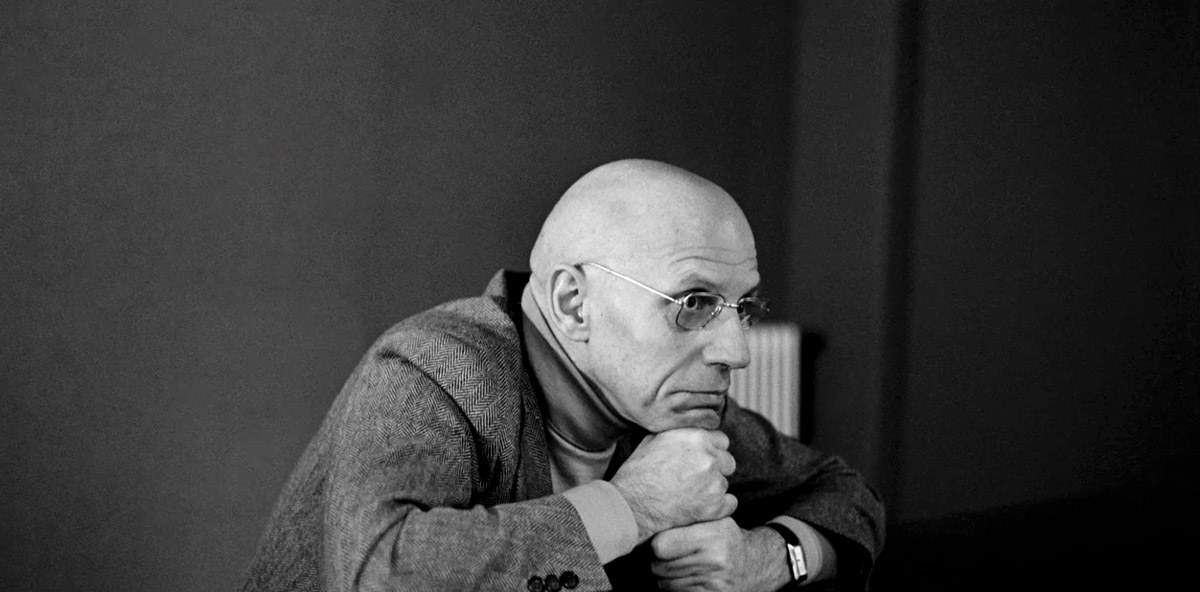

Michel Foucault (1926–1984)

Foucault revolutionized the way we think about power, knowledge, and institutions. Rather than viewing power as something simply held by authorities, Foucault saw it as embedded in discourse, knowledge, and everyday practices. His studies revealed how prisons, hospitals, schools, and even sexual norms shape how we understand ourselves.

In works like 'Discipline and Punish' and 'The History of Sexuality', Foucault explored how societies control individuals through “bio-power” and surveillance. He argued that knowledge is not neutral—it serves power structures and shapes identity.

Foucault’s influence extends across sociology, history, cultural studies, and queer theory. He blurred the lines between philosophy and critique, asking unsettling questions about how truth is constructed and whose interests it serves.

Lao Tzu (Approx 400-600 BCE)

Though Western philosophy dominates academic curricula, Eastern philosophy has shaped billions of lives—and Lao Tzu is one of its foundational figures. His ideas formed the basis of Taoism, a philosophy centered on oneness with nature or 'the way'.

He emphasized the importance of simplicity, patience and compassion- aka his '3 treasures'. In his succinct yet profound work the 'Tao Te Ching' or the book of the way, he lays out a simple, beautiful framework for achieving balance and content in life.

Rather than metaphysical speculation, Lao-Tzu focused on effortless action and 'going with the flow of life'. His teachings remain central to East Asian cultures and are increasingly recognized as rich philosophical contributions in their own right.

Final Reflection: Why These Thinkers Still Matter

Across centuries and civilizations, these 20 philosophers confronted the most profound questions of human existence: Who are we? What can we know? How should we live? Each offered a lens—a framework to navigate reality, selfhood, and society.

Whether it’s Plato’s ideals, Descartes’ rationalism, Nietzsche’s provocations, or Beauvoir’s liberation, these thinkers challenge us to examine our assumptions and push the boundaries of thought.

And perhaps that’s philosophy’s greatest gift—not just in answers, but in the courage to ask better questions.