Understanding Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder—once widely referred to as manic depression—is a serious mental health condition that causes a person to experience intense emotional states. These episodes range from extreme highs, known as mania or hypomania, to profound lows, typically defined as depressive episodes. These mood shifts are not just the common ups and downs that most people encounter—they are severe enough to interfere with daily functioning, relationships, and overall well-being.

For individuals living with bipolar disorder, life can feel like a pendulum swinging between two emotional poles. During periods of elevated mood, people may feel unusually energized, overly confident, or intensely irritable. These episodes often bring changes in behavior, energy levels, sleep patterns, and even thought processes. Conversely, depressive phases may bring overwhelming sadness, lack of motivation, fatigue, and a deep sense of hopelessness. Between these episodes, many individuals return to a relatively balanced state.

The term “manic” specifically refers to those heightened emotional states when a person becomes excessively excited, euphoric, or agitated. These episodes often lead to impulsive decisions, risky behaviors, and, in more severe cases, delusions or hallucinations—meaning they might believe in things that aren’t real or see or hear things that don’t exist. It's estimated that approximately 50% of individuals experiencing mania develop some form of psychotic symptoms during that time.

On the less intense end of the spectrum, “hypomania” presents with similar energetic and euphoric symptoms but without the delusions, hallucinations, or significant disruptions to day-to-day life. While still a noticeable shift in mood and behavior, hypomania typically doesn’t spiral into crisis.

When someone is in a depressive episode, they may feel drained of energy, plagued by feelings of worthlessness, and incapable of enjoying life. These symptoms align closely with major depressive disorder (also known as clinical depression), which differs from bipolar disorder in that it lacks any manic or hypomanic phases.

Interestingly, many people living with bipolar disorder spend far more time dealing with depressive symptoms than they do with manic or hypomanic ones. The depressive phases can last longer and hit harder, making them the more commonly experienced side of the disorder.

Variations of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is not a one-size-fits-all diagnosis. There are multiple types, each with its own distinct characteristics and criteria. Understanding the different types is essential for proper treatment and support.

Bipolar I Disorder

This is considered the most intense form of bipolar disorder. People with Bipolar I experience dramatic mood swings that include at least one manic episode lasting a week or more, or so severe that immediate medical attention is required. These manic episodes are usually followed by significant depressive episodes that last at least two weeks. The manic behavior in Bipolar I can be disruptive enough to affect work, relationships, and personal safety.

Bipolar II Disorder

Those diagnosed with Bipolar II also endure fluctuations between highs and lows, but the high phases never escalate into full-blown mania. Instead, they experience hypomanic episodes—elevated moods that are less severe and don’t usually lead to hospitalization. Depressive episodes, however, are just as severe as those in Bipolar I, and they often dominate the overall experience of the illness.

Cyclothymic Disorder (Cyclothymia)

Cyclothymia is marked by a more chronic but less severe form of bipolar symptoms. Individuals with this condition alternate between periods of mild depressive symptoms and hypomanic symptoms. These shifts must persist for at least two years in adults—or one year in children and teens—for a diagnosis. While the highs and lows don’t meet the full criteria for Bipolar I or II, they still disrupt life and can evolve into more serious patterns over time.

It’s also important to understand that any form of bipolar disorder can become more unstable when substance use is involved. Misuse of alcohol or drugs tends to intensify symptoms, provoke more frequent episodes, and complicate treatment. This co-occurrence is sometimes referred to as a “dual diagnosis,” and it requires integrated care that simultaneously addresses both the mood disorder and the substance use disorder.

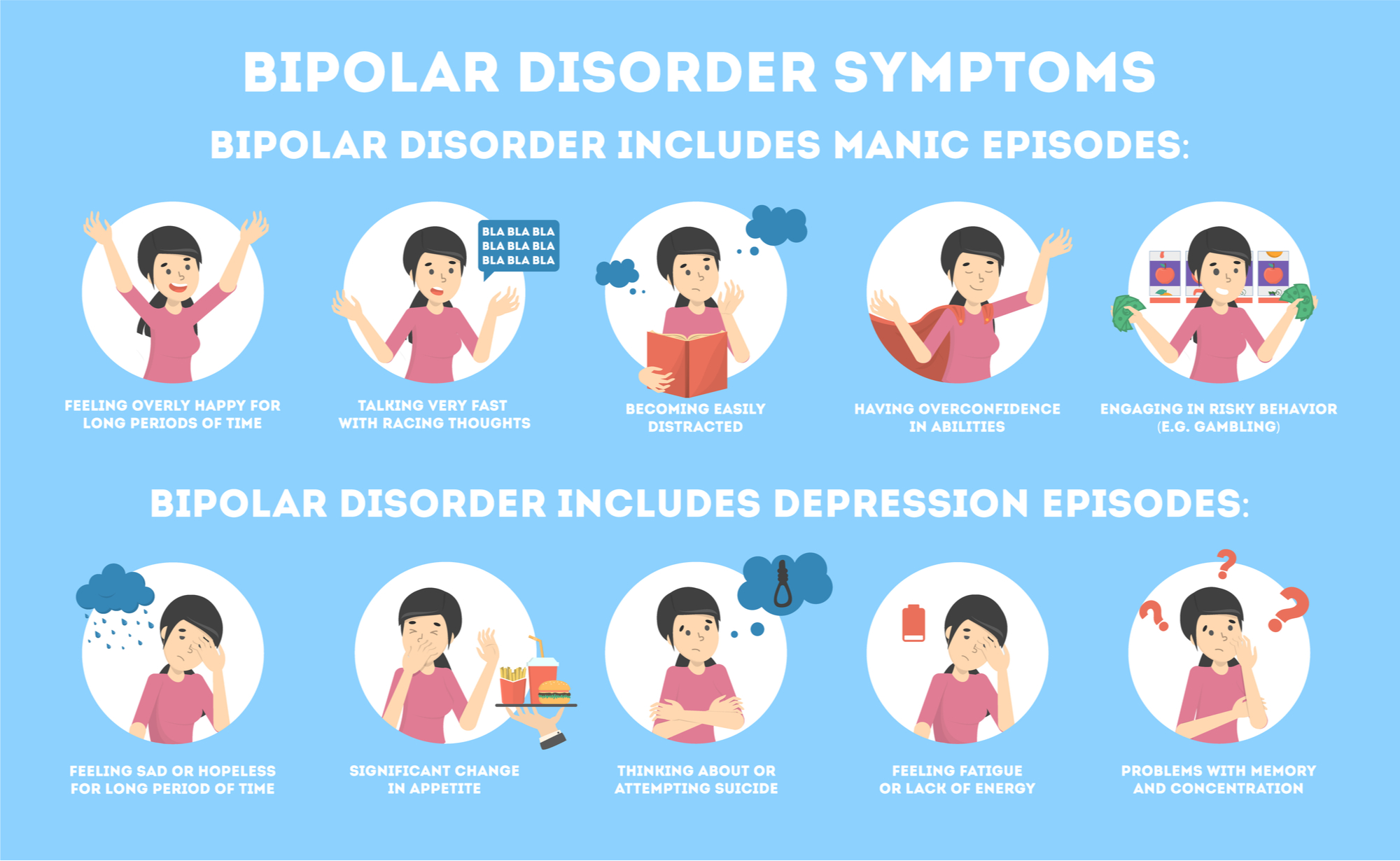

Signs and Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is characterized by sudden, dramatic shifts in mood. These changes don’t always follow a predictable pattern. For some individuals, a manic or depressive state can last weeks, while others may experience rapid changes within a single day. Episodes can recur over months or years, and the frequency and intensity can differ greatly from person to person.

The degree of severity may also change over time. Some people might begin with mild symptoms that escalate gradually, while others might face abrupt and intense shifts from the start.

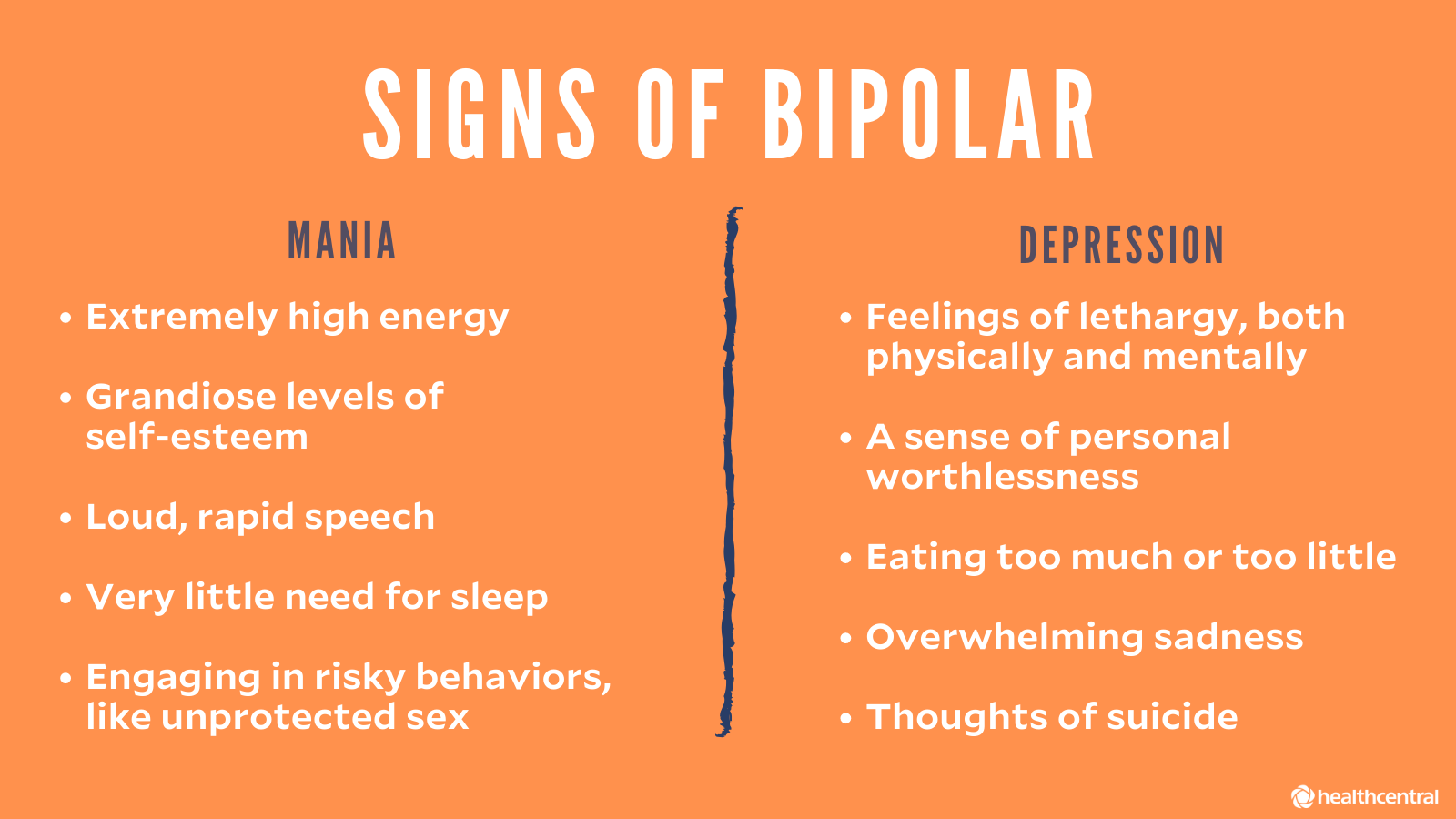

Key Symptoms of Mania (The Elevated Phase):

-

Heightened mood or euphoric feelings

-

A sudden switch from happiness to anger or irritability

-

Physical restlessness or agitation

-

Rapid or pressured speech

-

Trouble focusing or staying on task

-

Decreased need for sleep

-

Excessively high libido

-

Engaging in overly ambitious or unrealistic plans

-

Poor decision-making, often involving financial or social risks

-

Substance abuse (especially stimulants or alcohol)

-

Inflated self-esteem or feelings of invincibility

-

Easily sidetracked or distracted

-

Noticeable reduction in appetite

Symptoms During Depressive Episodes (The Low Period):

-

Persistent fatigue or lack of energy

-

Deep feelings of sadness or despair

-

Beliefs of worthlessness or failure

-

Loss of interest in hobbies or activities

-

Difficulty focusing or remembering things

-

Speaking slowly or seeming mentally sluggish

-

Low or nonexistent sex drive

-

Anhedonia—the inability to feel joy

-

Frequent crying spells

-

Indecisiveness and self-doubt

-

Irritability or social withdrawal

-

Oversleeping or inability to sleep

-

Changes in eating habits—eating too much or too little

-

Suicidal thoughts or planning

-

Suicide attempts or self-harming behaviors

These symptoms not only disrupt daily functioning but can be deeply distressing to both the individual experiencing them and the people around them. Recognizing and understanding these signs is the first step in seeking appropriate help and treatment.

What Leads to Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder doesn’t have a single, identifiable origin. Instead, it’s influenced by a complex web of factors—genetic, biological, and environmental. Researchers continue to explore how these elements interact to shape a person’s susceptibility to the disorder.

In many cases, genetics plays a central role. People with a family history of bipolar disorder are at significantly greater risk of developing the condition themselves. This doesn't mean it's inevitable, but the inherited vulnerability is notable.

There are also theories about structural and chemical differences in the brain of someone with bipolar disorder. For example, abnormalities in the brain’s neurotransmitters—chemicals that regulate mood and emotion—may contribute to the erratic mood swings. However, scientists still don’t fully understand the exact neurological changes that cause bipolar disorder to develop or escalate.

Environmental stressors, such as trauma, prolonged psychological distress, or significant life changes, can act as triggers for people who are predisposed. These events don’t directly cause bipolar disorder but may be the spark that brings latent symptoms to the surface.

Who Is at Risk for Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder most commonly makes its first appearance in late adolescence or early adulthood. However, it can sometimes manifest earlier during childhood, though this is less frequent. While both men and women are equally likely to be diagnosed, the expression of symptoms can vary between genders.

For example, women tend to experience more depressive episodes than men and are more likely to undergo what’s known as “rapid cycling”—where four or more mood episodes occur within a single year. Additionally, hormonal fluctuations, particularly during pregnancy or postpartum, can sometimes intensify or trigger symptoms in women.

The risk of developing bipolar disorder also increases when it runs in the family. A close relative—such as a parent or sibling—who has the condition raises your likelihood, especially when combined with other risk factors like high stress levels or a history of trauma.

Substance abuse is another major contributing factor. The use of alcohol, recreational drugs, or even certain medications can provoke symptoms or make them worse. Some individuals attempt to self-medicate their moods with substances, unknowingly worsening the underlying disorder.

Other health issues, such as anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), thyroid conditions, and migraines, are also commonly seen alongside bipolar disorder—particularly in women. The interplay between physical and mental health challenges often makes diagnosis and treatment more complex.

How Is Bipolar Disorder Diagnosed?

If you or someone you know is showing signs of bipolar disorder, the first step is consulting with a qualified healthcare provider—ideally a psychiatrist or a family doctor with mental health experience. The process involves a thorough assessment of symptoms, personal history, and family background.

The healthcare professional will conduct a psychiatric evaluation to understand the person’s current mental state and how their symptoms have evolved over time. They will ask detailed questions: Have there been unusual mood swings? How long do these periods last? How disruptive are they to daily life?

It’s also important to rule out other possible causes. For instance, an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) can produce symptoms similar to depression. Substance use, certain medications, or neurological disorders can also mimic mood-related symptoms, which is why a complete medical and psychological review is essential.

Diagnosing bipolar disorder can be particularly tricky in children and adolescents. Many of their symptoms overlap with other conditions such as ADHD or conduct disorders, and emotional outbursts may be mistakenly attributed to typical developmental behavior.

Doctors often rely on input from family members and close friends to understand how a person behaves outside of clinical settings. Observations about changes in sleep, mood, energy, and decision-making can provide crucial context for an accurate diagnosis.

If bipolar disorder is suspected in a child or teenager, it’s important to seek out a pediatric psychologist or psychiatrist with specific expertise in mood disorders during youth. Early diagnosis can significantly improve long-term outcomes.

Treating Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is manageable, but it requires consistent and often lifelong treatment. The primary goal is to stabilize mood swings and reduce the frequency and intensity of episodes. Treatment usually combines medication, therapy, lifestyle changes, and support systems.

Medication Options

Medications are the first line of defense and usually include a combination tailored to the individual's needs:

-

Mood stabilizers like lithium, lamotrigine (Lamictal), valproate (Depakote), or carbamazepine (Tegretol) help prevent mood extremes.

-

Antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine (Seroquel), lurasidone (Latuda), cariprazine (Vraylar), or olanzapine (Zyprexa) are used especially when hallucinations or delusions are present.

-

Antidepressants may be added but must be monitored carefully, as they can sometimes trigger mania if used alone.

-

Antidepressant-antipsychotic combinations are used in some cases to address both depressive and manic symptoms.

-

Anti-anxiety or sleep aids, often benzodiazepines, can be prescribed for short-term relief during episodes.

Since finding the right medication can involve some trial and error, ongoing communication with a psychiatrist is crucial. Abruptly stopping medications or adjusting doses without guidance can lead to a rebound of symptoms or withdrawal effects.

Pregnant or breastfeeding women must consult closely with their doctors to weigh the risks and benefits of medication use. Some drugs may be unsafe during pregnancy, requiring alternative plans.

Psychotherapy Approaches

Talk therapy plays a critical role in bipolar disorder management, offering individuals a better understanding of their condition and tools to navigate it:

-

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) helps establish routines for sleep, eating, and social interaction to reduce mood fluctuations.

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps patients identify and reframe negative thoughts and behaviors, while learning to manage stress and avoid triggers.

-

Psychoeducation is vital not just for the individual but also for family members, offering knowledge that improves empathy, preparedness, and support.

-

Family-Focused Therapy works to strengthen communication, identify early warning signs of mood episodes, and develop joint coping strategies.

Additional Treatment Methods

-

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) is used in treatment-resistant cases. Though its name may sound alarming, modern ECT is safe, controlled, and often effective when medications and talk therapy fail. It works by delivering small electrical currents to the brain under medical supervision, triggering a brief seizure that can reset neural activity.

-

Acupuncture has gained attention as a complementary therapy, particularly for its potential effects on depressive symptoms, though more research is needed.

-

Nutritional supplements, including omega-3 fatty acids or magnesium, are sometimes used. However, these are unregulated and can interfere with prescribed treatments, so it’s essential to discuss any supplements with a healthcare provider.

Healthy Lifestyle Changes

Supporting your treatment plan with healthy daily habits can have a big impact:

-

Maintain regular physical activity

-

Stick to consistent routines for eating and sleeping

-

Track your moods and triggers in a journal or app

-

Seek out social connections and community support

-

Practice stress-reduction techniques like meditation or deep breathing

-

Avoid alcohol and recreational drugs, which can destabilize mood

-

Develop hobbies and interests that foster positivity and balance

By combining these approaches, many people with bipolar disorder are able to manage their symptoms, lead fulfilling lives, and reduce the frequency and severity of their mood episodes.

The Link Between Bipolar Disorder and Suicide

Among the most serious complications of bipolar disorder is an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Unfortunately, without proper treatment and support, some individuals struggling with this condition may consider or attempt to take their own lives.

Recognizing the red flags early can be life-saving—not just for the individual but also for the people around them. Loved ones, friends, coworkers, and even healthcare professionals should be attuned to these indicators and respond with urgency.

Here are some warning signs that may suggest someone with bipolar disorder is at risk of suicide:

-

Withdrawal from social interactions and self-isolation

-

Talking about death, dying, or expressing a desire to disappear

-

Expressing feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, or unbearable emotional pain

-

Acting recklessly or engaging in risky behavior without concern for consequences

-

Sudden increase in drug or alcohol use

-

Sudden calmness or happiness after a period of depression (this may signal a decision has been made)

-

A noticeable decline in interest in activities, responsibilities, or personal care

-

Giving away cherished possessions or making final arrangements

-

Crying frequently or showing signs of emotional shutdown

-

Talking slowly, or expressing deep emotional numbness

It’s important to remember that suicidal thoughts can emerge during both depressive and manic episodes. In mania, impulsive behavior can escalate quickly and lead to dangerous actions. In depression, the heaviness of emotional despair can make death seem like the only escape.

If someone shows any of these signs, seek immediate help. Contact emergency services, reach out to crisis lines, or get them to a mental health professional as soon as possible. Don’t ignore or downplay suicidal talk—even if the person insists they're fine.

What’s the Difference Between Mania and Hypomania?

One of the most complex aspects of bipolar disorder is understanding the nature of manic and hypomanic episodes. While both involve heightened energy and mood elevation, there are key differences in their intensity, impact, and potential consequences.

Hypomania: The Subtle Surge

Hypomania is often described as a less severe form of mania. Someone experiencing hypomania may feel unusually upbeat, energetic, or confident. They might seem more sociable, productive, and creatively inspired. To the outside observer, it can even look like the person is simply having a really good day.

But beneath the surface, hypomania can be a double-edged sword. It can impair judgment, disrupt sleep patterns, and cause emotional instability. And the real danger is that hypomania can escalate into full-blown mania or plummet into deep depression without warning.

Mania: When High Becomes Hazardous

Mania is far more intense and disruptive. It often includes:

-

Extremely elevated mood, or conversely, heightened irritability

-

A flood of racing thoughts and speech

-

Drastically reduced need for sleep, sometimes going days with little or no rest

-

Risk-taking behavior, such as reckless spending, unsafe sex, or erratic driving

-

Grandiose beliefs—feeling invincible or convinced of supernatural abilities

-

Impulsivity and lack of awareness of consequences

-

In severe cases, psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions

When psychosis enters the picture—such as hearing voices, seeing things, or holding bizarre beliefs—it's no longer hypomania. At that point, it’s classified as mania and typically requires immediate medical attention.

People in manic states often don't recognize their behavior as problematic. They might resist treatment or become defensive if others express concern. That’s why it's often family members or close friends who first notice the signs and encourage them to seek help.

One of the biggest challenges is that the line between hypomania and mania can blur—and the transition from one to the other may be rapid and unpredictable.

Living With Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder is an ongoing journey that requires patience, resilience, and support. It doesn’t go away with a single round of medication or therapy—it’s a lifelong condition that must be continuously managed.

But with the right tools in place, many people with bipolar disorder not only cope—they thrive. They build careers, nurture relationships, pursue creative passions, and lead fulfilling lives. The key is awareness: knowing your triggers, sticking to your treatment plan, and surrounding yourself with people who understand and support you.

If you're someone living with bipolar disorder, or caring for someone who is, you're not alone. Millions of people around the world walk this same path. And while the journey isn’t always smooth, it can absolutely lead to a meaningful, empowered life.